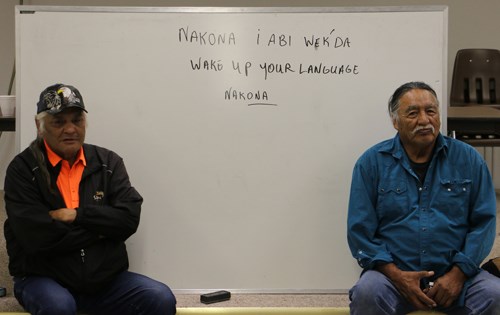

The Nakota language is slowly being lost, but two local native speakers of the language – Armand McArthur of Pheasant Rump and Peter Bigstone of Ocean Man – are hoping to spread the knowledge passed down to them by their relatives to a new generation of Nakota speakers.

Traditionally the Nakota language was gender specific, meaning male and female counterparts would ask questions differently or refer to something in different terms; today, the language is more forgiving according to McArthur and Bigstone as they say a male maybe only learned the language from their grandmother or a female may have learned the language from their grandfather. For them the most important aspect of the efforts they are putting into teaching the language to a new generation is that the new generation open themselves to learning it in any form.

“The language is part of the Law of the Land given to us from the Creator, God,” McArthur stated. “It’s very important for us to know our language as a people. Language is a big part of our culture and traditions.”

“The Law of the Land is supreme: We must be at peace with ourselves, we must find peace with our family, we have peace with all plant nations, and peace with all animal nations. We all come from one, so plants and animals are our relatives as well. It’s a very inclusive language.”

“We need to go back to the Law of the Land as it pertains to First Nations,” McArthur continued. “The law today is a foreign law to us, it applies to us, but even today many of us don’t know how to cope with it. We don’t have that understanding. And the Law of the Land is protected by the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Treaties that followed.”

Language is a large part of culture and tradition for any peoples, but following Residential Schools and the attempted assimilation of First Nations people to the “Canadian identity” that the government was perpetuating at the time many First Nations’ languages and cultural practices were lost. There are now movements focused on recovering and teaching these lost languages and cultural practices.

“My grandfather taught me the language and I was able to retain it through the Residential Schools,” Bigstone explained.

The Nakota language itself was not a written language and knowledgeable individuals who have continued to speak it are the source for it today. Linguists have developed an alphabet based on the English alphabet to be used while learning the language, while a Nakota dictionary has also been developed.

“It’s good to have those resources, but it’s important to learn where you can hear it as well. There are subtleties between words that look similar when written, but are pronounced differently and mean very different things,” McArthur explained.

Bigstone added, “It’s important to get our culture back. Sometimes it feels like we’re fighting a losing battle because the younger generation doesn’t always want to put the time in to learn it. But, it’s worth it if even just one will continue it on.”

Bigstone continued, “European languages and languages of immigrants now coming here are all protected, but Nakota and other First Nations languages are disappearing.”

Peter McArthur, who helped organize the three-day course held in Kisbey last week, agreed: “We need to bring people together and to develop a respect for each other. There needs to be reconciliation and the only way to do that is for everyone to be involved.”

The language is relatively easy to comprehend. Each word comes from a root word, which with a little thought and knowledge of the language makes sense when explained. For example, the word for snow is “wa,” while the word for hail is “wasu.” “Wa” meaning snow and “su” meaning stone, thus hail is known as “snow stone” when directly translated to English.

The language can also adapt and new words be developed by simply following the natural way the words come together in describing the item.

One of the participants in the three-day language course, Joan McArthur of Pheasant Rump, agrees that language is extremely important and must be retained and taught to younger generations: “Bringing the language back is important – for any culture language is important, when you look at the French, German, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, anyone, they’re strongly built cultures who have a strong connection to their language. Language grounds you, so working together to understand language and cultural ways builds that strength.”

She continued, “Language allows us to be grounded, to have our values, our cultural and traditional ways, it connects us to what we did in our pasts. If our language is lost then we don’t know where we come from and we as a people will be lost. Language is our roots, it connects us to our past relatives. Whenever I hear Nakota, here in the classroom or elsewhere, I can hear my dad speaking it. It’s very comforting, but it’s very emotional as well.”

Bigstone and Armand McArthur hope to develop a language course for the winter and are hoping to work towards immersive classes where students are surrounded by the language.